In the US, copyright is free and automatic. According to the US copyright office, “Copyright is a type of intellectual property that protects original works of authorship as soon as an author fixes the work in a tangible form of expression.”[1] Whether the work is offered for free or for sale does not affect the copyright. The copyright holder has the exclusive rights to distribute the work, to edit, adapt, or change the work, and to use the work for commercial purposes or other financial gain. Creative Commons licenses allow copyright holders to grant one or more of those rights to users, provided the creator is credited for the original work.

The broadest Creative Commons license is Attribution (CC BY). It grants users all of the same rights as the original creator, as long as the creator is given credit for creating the original work. All CC licenses begin with and include Attribution, but limit the user’s’ rights to share, adapt, or profit from the work in some way.

The Attribution-ShareAlike license (CC BY-SA), allows adaptations and commercial use, but requires all users to share their work with the same license as the original.

The Attribution-NonCommercial license (CC BY-NC), allows adaptations but prohibits users from using the work or any derivatives for profit or other commercial purposes.

The Attribution-NoDerivatives license (CC BY-ND) limits users ability to change or adapt the work except for personal use, but the license does not restrict the user’s rights to distribute the work, including for sale or for other commercial purposes.

The Attribution-NonCommercial ShareAlike license (CC BY-NC-SA) grants the right to adapt the work provided it is shared with the same license. This license does not allow users to profit from or otherwise use their adaptations commercially.

The Attribution-NonCommercial No-Derivatives license (CC BY-NC-ND) grants only the right to use the work and does not allow adaptations, derivatives, or commercial use.

What license might a knit designer use if they are offering a pattern for free? Susanna IC has a copyright notice on her website. The license for all her free patterns is CC BY-NC, so users can adapt and share the work with attribution, but not for profit or other commercial purposes.[2] She retains the copyright for all her paid patterns.

Another knit designer, Laura Semesky, has granted users the CC BY-NC-SA license for her Winter Is Coming scarf pattern, which allows users to use and adapt the work non-commercially as long as they credit the designer and share the adaptations with the same license as the original.[3]

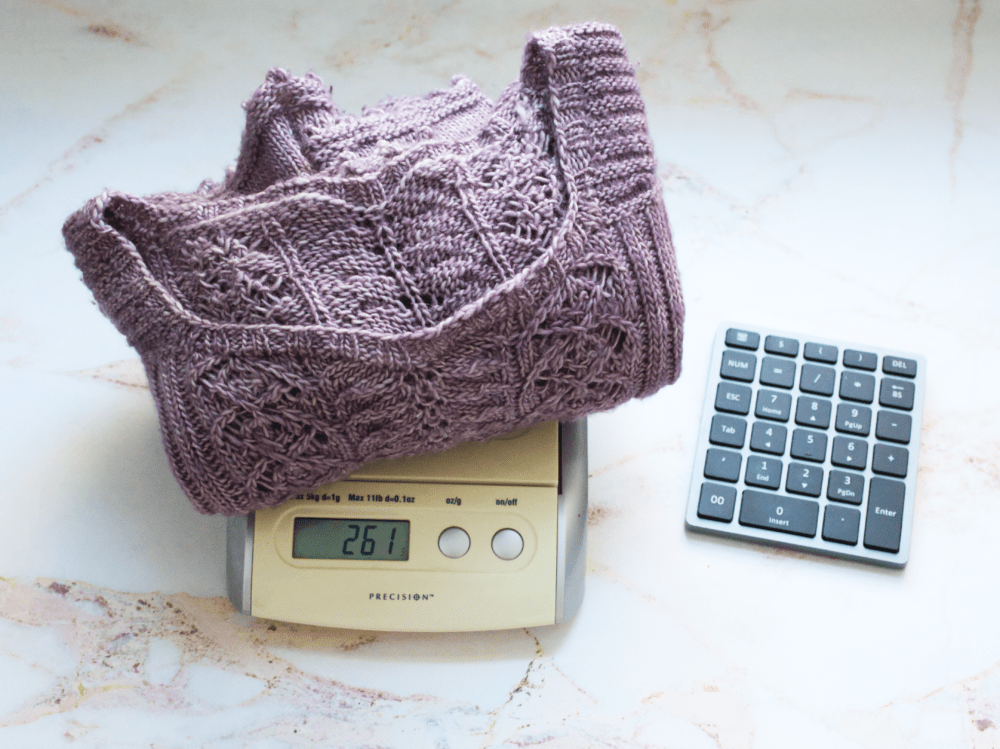

I have just amended my free Voyager Shawl pattern to have the CC BY-NC-SA license also. I developed this pattern the same way as all my others, with tech editing and test knitting, but I made it free so people could see an example of my work in my portfolio.

There are a lot of free knitting patterns available, but many of them don’t use Creative Commons licenses. This could be because the designers are unaware of these licenses, but we shouldn’t assume so. The designers may just want to retain all their rights as the copyright holder.

Some designers use free patterns to drive traffic to their websites, or as a thank you for signing up for their mailing list, both commercial purposes that are protected by copyright.

With the large number of free knitting patterns on the internet it’s important that knitting pattern creators and users understand copyright and Creative Commons licenses. Check out the Creative Commons website to find out more.

[1] Office, U. C. (n.d.). What is Copyright? | U.S. Copyright Office. https://www.copyright.gov/what-is-copyright/

[2] ArtQualia | Designs by Susanna IC | Copyright Notice. artqualia.com/copyright%20notice.html.

[3] “Winter Is Coming Pattern by Laura Semesky.” Ravelry, http://www.ravelry.com/patterns/library/winter-is-coming-9.