Have you ever wondered how designers arrive at the recommended yardage listed in a pattern? Are you designing a sweater and wondering how to accurately list the yardage for sizes that haven’t been knit yet? Or maybe you are changing the gauge or length of a sweater you’re knitting and want to make sure you don’t run out of yarn? In all of these situations you can estimate how much yarn you’ll need using a swatch, a kitchen scale, the information from your yarn’s ball band, and a calculator or spreadsheet. This is how I do it.

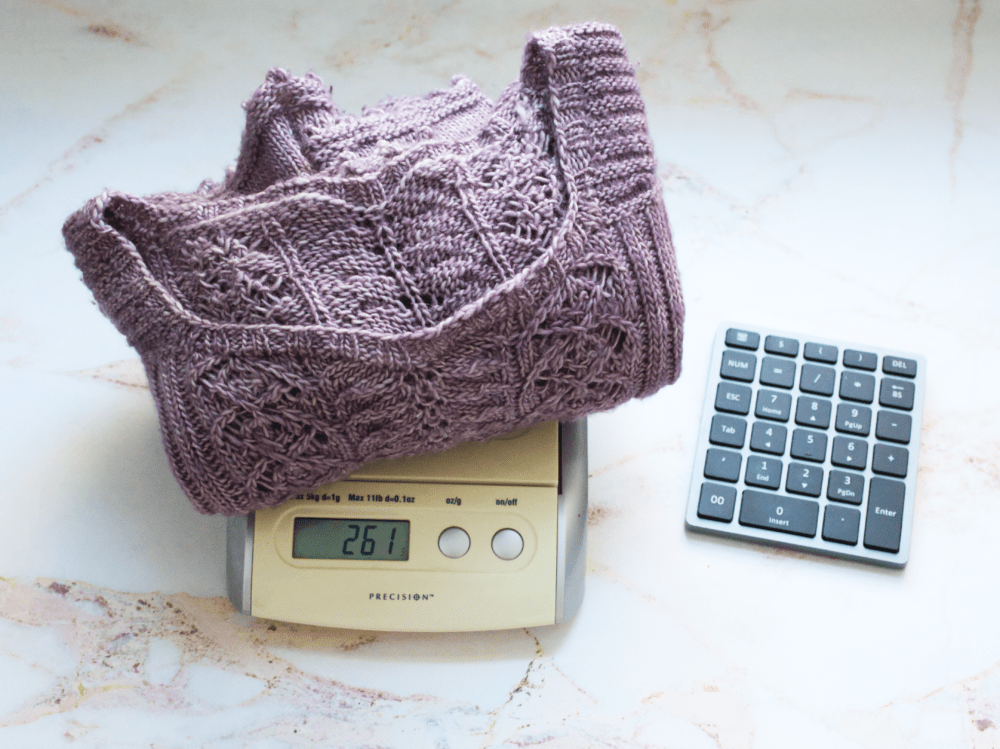

First, determine how much yarn it takes to make a square inch or square centimeter of your knitted fabric. You can start with a large rectangular swatch or an entire garment. Weigh your swatch or sample using the kitchen scale. I like to use the weight in grams because it’s a smaller unit of measure than ounces, and ball or skein weights are usually given in grams.

Next, determine the area of your swatch or sweater. If your swatch is a square or rectangle you can multiply the length by the height to determine the area. For example, if your swatch measures 8 x 8 inches the area is 64 inches. (If you’re more comfortable with metric go ahead and use centimeters for all measurements instead.) Divide the area by the weight. Let’s say your swatch weighs 10 grams. 64/10 = 6.4. It takes 1 gram of that particular yarn to make 6.4 square inches of that particular fabric. If you wanted to add 2 inches in length to a sweater with a circumference of 40 inches that’s 80 square inches. 80/6.4 = 12.5. You would need an additional 12.5 grams of yarn.

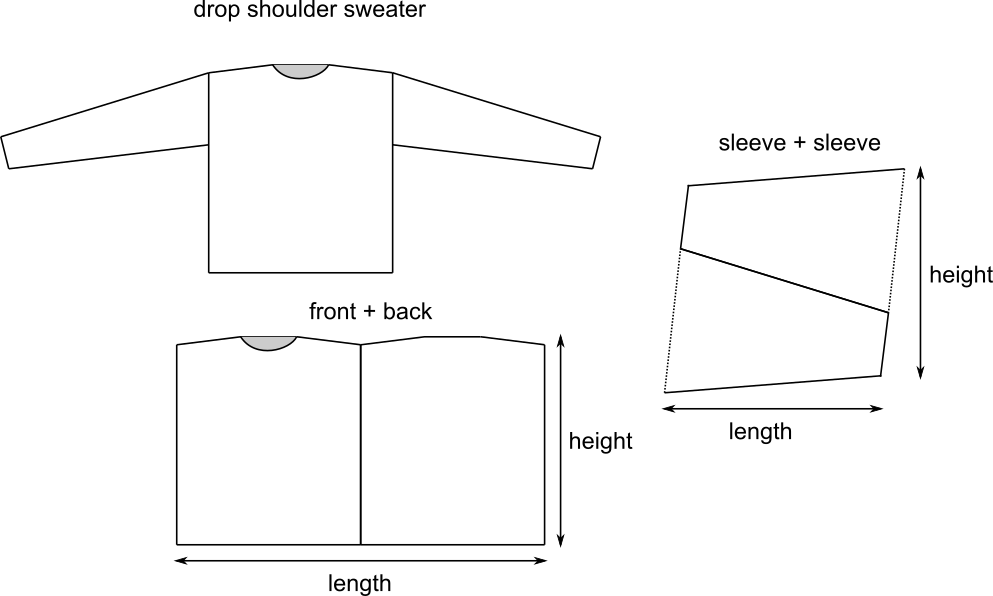

To find the area of an entire sweater I reduce the design into simple shapes like rectangles and parallelograms as shown in the illustrations below, and multiply the length by the height to find the area of each shape.

Drop Shoulder

A drop shoulder sweater is the simplest design for finding the area. The front and back are rectangles and there are two trapezoids for the sleeves. Add the length and width of the two sleeves together to make one parallelogram. If there is a collar it is probably a rectangle also, and you can add the length to the height to find its area.

Raglan Yoke

If you take a raglan sweater off the needles at the underarm and lay it out flat you’ll see how the yoke can be simplified into a rectangle. Multiply the chest width by the upper sleeve width before the underarm cast on to find the area of the yoke. Unless it’s a deep V or a scoop neck I don’t subtract anything for the neck. This just adds a little buffer to the yardage. The area of the body below the underarm and the sleeves below the shoulder can be calculated in the same way as the drop shoulder sweater.

Round Yoke

For round yokes, first determine the radius of the yoke by adding half the neck width to the yoke depth, square the radius, then multiply by pi. This will give you the area of the yoke. The area of the sleeves and the body below the underarms will be the same as the raglan sweater.

Set-In Sleeve

A set-in sleeve sweater will have a few more shapes than the others. The sleeve caps can be treated as trapezoids the same way as the sleeves and added together to create one parallelogram. The body of the sweater below the underarms can still be treated as two rectangles, but if there is significant waist shaping you may wish to break the top and bottom into trapezoids and add them together. The yoke can also be treated as a trapezoid, and adding the front and back together will make a parallelogram.

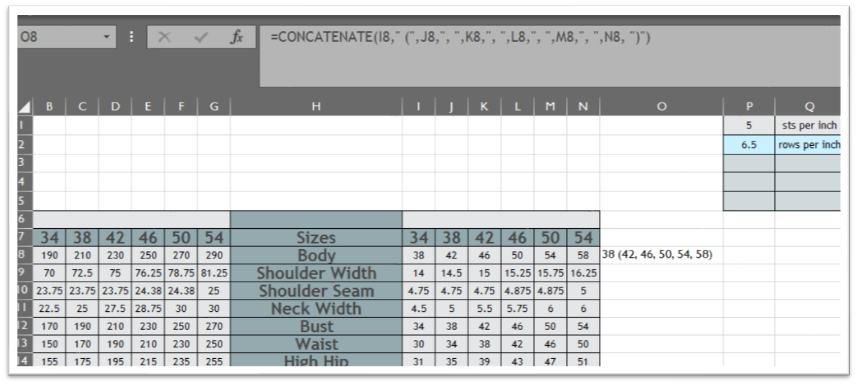

After you have determined the area of your sample you can find how many grams of your yarn it takes to make 1 square inch of your fabric by dividing the area of the sample by the weight of the sample. You can then multiply the grams per square inch by the total area of every other size in your pattern. This will tell you how much of that particular yarn it takes to make each size by weight, but you should also convert the weight into yards to make the estimate useful to knitters who want to use a different yarn.

Using the information from the ball band of your sample yarn, divide the weight of one skein by the yards per skein to find the yards per gram, then multiply the yards per gram by the weight of each size. This will give you the yardage needed for each size. You can also estimate the number of skeins needed for each size by dividing the total weight by the weight of one skein and rounding up to the nearest whole number.

You can see from the illustrations above that the area measurements are not exact, and each knitter’s tension will affect the amount of yarn used also. These are only estimates, but you want to be sure that your knitters will not run out of yarn before completing their projects, so it is a good idea to add a buffer to the recommended yardage, which is usually 10%, but could be more or less depending on the design.

Estimating yardage is just one of the tech editing services I offer. Yardage estimates are included with every grading job I do, but I can also check your yardage estimates or calculate the yardage for you when I tech edit your pattern. Just let me know that’s a service you’re interested in and tell me the size and weight of your sample. I would love to know what you think of this method of estimating yardage in the comments!

Thank you for knitting!