When knitting cardigans, stitches are often picked up and worked onto the front edges of the sweater for the button bands and button hole bands. Perfectly serviceable bands are created this way, and if care is taken to pick up the correct amount of stitches and work at the right gauge, the bands will work, but there are a few things that can go wrong. The bands may pucker (too few stitches picked up) or flare (too many stitches picked up). Ribbing, seed stitch, and garter stitch, all excellent band choices for their non-curling properties, have a tendency to spread width wise, which can cause perpendicular bands to droop.

One way to avoid all of these problems is by working the bands in the same direction as the body of the sweater, parallel to the fronts. The same number of rows can be worked on the band as there are on the front of the cardigan, but at a tighter gauge, giving the bands just the right amount of stretch. Seed stitch, ribbing, and garter stitch are given a firm vertical tug, keeping their width-wise spread in check. A different color can be used, or even a different yarn. Bands like this are often sewn on, or sometimes stitches are picked up along the sweater fronts and bound off as the band is attached. I think the side-to-side join is the neatest and easiest way to attach parallel front bands, but I rarely see it used, so I’ve illustrated the technique in steps below.

Setup: Start by casting on the number of stitches needed for your band. Double pointed needles or short straight needles 1 or 2 sizes smaller than the needles used for the body of the sweater will work best.

Step 1: Insert the needle into the edge of your cardigan from front to back.

Step 3: Remove the loop from the needle and pull out enough yarn to comfortably knit the next 2 rows. The excess length will be removed later so this does not need to be exact.

Step 4: Work the first wrong-side row of the band with the bottom half of the loop.

Step 5: Work the second right-side row of the band with the top half of the loop and pull tight so the band is snugged up against the front.

Repeat steps 1 through 5 for the length of the fronts. Two rows are worked for every picked-up loop, so you will have to skip every second row on the sweater front for the band to have the same number of rows. If you are working a round neck cardigan, both bands can be worked first and continued into the neck band. For v-neck cardigans, the bands can continue around the neck edge to be joined at the back neck.

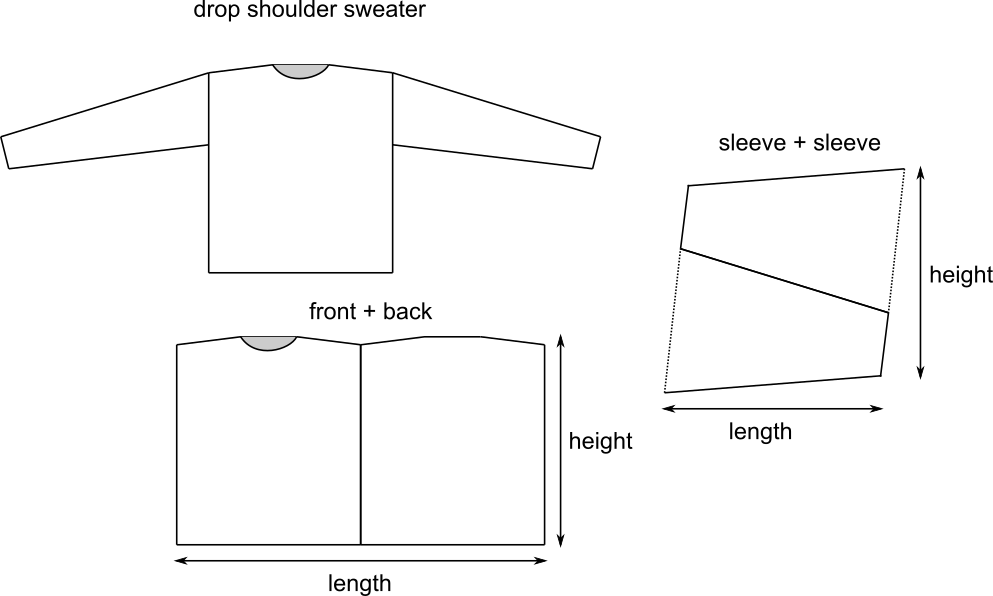

Cardigans aren’t the only use for the side-to-side join! Anywhere you would would like to attach a parallel piece of knitting to an already finished piece this method will work. The cover photo and the photos below are examples of sweaters that I made using this technique.

Let me know in the comments if you’ve seen this method before or if you’ve tried it yourself.

Thank you for knitting!